“The great power, however, rests in uncertainty, in the conviction that there are no solutions but only transformations and changes of form … that, to me, is not fatalism, it is a very big yes to life.” (Christoph Schlingensief)

To comprehend Schlingensief in a few sentences, to describe him in a single page strikes me as impossible. His work and he himself were so fascinating because he always acted emotionally and yet was invariably perfectly clear in the use of, and engagement with, the media conditions and communicative abilities of our time. He didn’t speculate, he confuted every expectation, he picked a fight, he didn’t use “coolness” or skepticism to stand aloof. He spoke of opacity and meant authenticity. In this way, his art created forever more interfaces with its environment, inevitably inviting people to interact with it.

Since the early years of the last century, art has come to work with greater and greater energy on its own boundaries and on dissolving the individual disciplines; in Schlingensief it became an instrument that, no longer requiring interpretation, was instead able to prove itself wrong. Schlingensief thus triggered a turning point at which art must define itself in a new way.

His Viennese container project Ausländer raus [Foreigners Out] attested to this redefinition of art, in which art in the classical sense failed to recognize itself because it suddenly found itself confronted with forms from reality shows, among other things. Working in the art context, Schlingensief successfully staged an aggressive intervention in political issues by employing form, style, and content in antithetical fashion: “Refuting [Jörg] Haider is impossible; doing a test run of Haider is possible.” Accordingly, the participants in his productions were not always actors but also included people directly affected by an issue: foreigners, former neo-Nazis, disabled people, etc. So he did test runs, as though in a laboratory, of what it means to stigmatize someone and to expel him from the country at the end of the day. Similar ideas drove his project of founding the party “Chance 2000” or the Church of Fear.

Art became a test laboratory. And it was only logical that he would say about the theater: that’s politics.

Schlingensief refused to see art as independent from life. The separation between art and life did not exist for him. In repealing the boundaries between the disciplines of art and the conduct of life, and in the gift that enabled him to use all means the modern world of media put at his disposal with absolute impudence, he turned art into an instrument, even a weapon. It allowed him to take specific stances and to interfere, to broach the issues of the day: that is, to use his art to make a difference in its social context, a form of action that ultimately found its most concrete realization in the opera village project, Remdoogo.

This impulse arose out of a conception of freedom he insisted on and claimed for himself. That is why he also permitted himself infringements that seemed to amount to breaches of rules, in the registers of content as well as style, and through them he did not create reality, as the theater is wont to claim it does, but attacked it, turning art into reality and vice versa.

I understand Schlingensief as someone who knew about the world, had a pronounced sense of his mission, and was always on air, always live. It seemed as though he was driven by a duty, a responsibility that cast a spell over everyone he met.

Schlingensief’s work has left a deeply profound imprint.

As theatrical productions of today’s world, informed by German traditions and yet of universal human validity in their moral high-mindedness, his works established a new iconography that tied art most closely to everyday life.

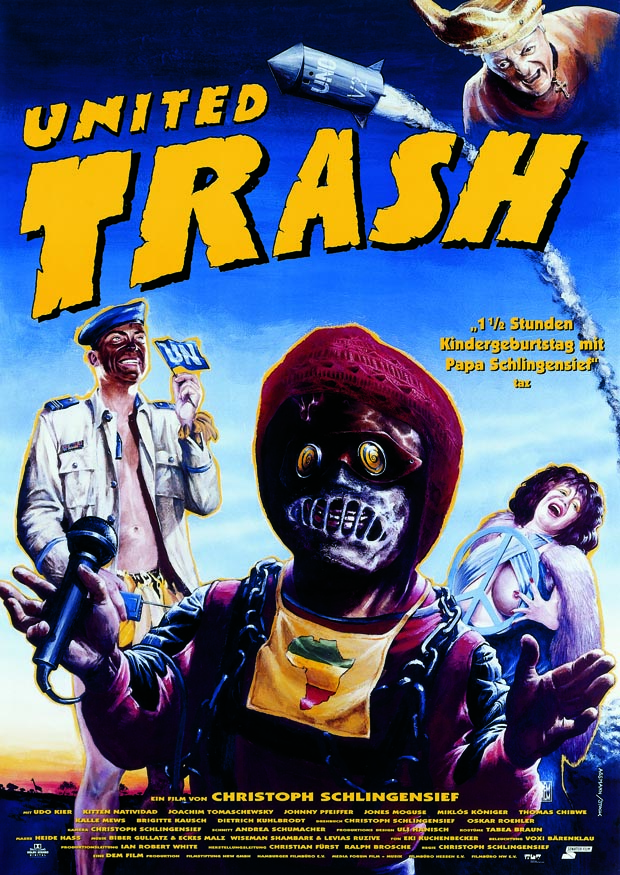

He generated new ways of grasping and looking at reality, new interpretations of art: nothing remained untouched in his work—Catholicism encountered the world of consumerism, different cultures collided, morality met immorality, systems were perverted into their opposites, he beat the entertainment industry at its own game and execrated the conventional publicly funded repertoire theater as an entertainment factory. He interwove all devices of art and put them to use. Film, for instance, the artistic means that was second nature to him, a technical instrument beholden to movement that allows for cuts, slashes, contortions, false perspectives, etc., also shaped the aesthetics of his later work, be it on stage, in the art space, in the public sphere, in the book.

His art is contradictory, without ideology, open. He shied away from nothing, took what he needed, from Goethe to Immendorf, from Nietzsche to Warhol, from Schoenberg to Jelinek, jumbling it up and patching it together into new shapes—a way of working that produced astonishing screenplays, texts, shows, installations. He was a congenial plagiarist, a DJ as well as VJ of art, something he acknowledged frankly and publicly. Truth, in its incredible complexity, rose up before us, and its power to amaze and affect us was ineluctable. Art, he thought, “becomes interesting when we face something we cannot altogether explain.”

So it was only logical that Christoph Schlingensief would go to Africa. Working there, he could kick something off, set something in motion, but he clearly recognized his limitations; the language and the different culture, to begin with, were barriers to understanding. Suddenly the only option was trust. Suddenly the only thing to do was to marvel in beauty. He created something, and in so doing engendered movement. And miraculously demonstrated that artistic thinking and action can move mountains and lead to insight, insight of which a self-possession that fights back, that can stand up, can be itself, believes its own ego and the other’s capable. This was most evident in his play Mea Culpa, where he flips death the bird with great serenity, declaring himself the creator of his own life.

Schlingensief made us shake and tear at our own perceptions until we were left unnerved, entranced, crazed, amazed. Together with the artist, who, often in the thick of it, acting as moderator, driving force, actor, seducer, took aim at a reality that seemed to have spun out of control.

A loving moralist, sickened by the German character, its past and its uncertain future (he once spoke of the putrid smell in Germany), but also by the opacity of the world in general; but which he could never have done, never wanted to do without this world—he simply loved it.

His “stomach was twisting itself into a knot,” he once called out to me via text message. Every single instance of injustice, every failure of understanding affected him personally, drained his body of its strength. He was like a seismograph, recording everything, needing his art for self-protection, a gifted chronicler of our time who used the means of art to render magnificent liberties (back) to life.

Elisabeth Schweeger for Christoph Schlingensief. A preprint from the book accompanying the German Pavilion © German Pavilion, Sternberg Press