Sunday, August 22, 2010, eight o’clock. Stunned by the news of your death that came yesterday—in the end, it was a surprise after all—and having slept only a few hours, I gaze into the morning sun, little big Scorpio brother, and find no way forward in my gloom. As though paralyzed, my mind keeps returning to something Bazon Brock made us take to heart: Death must be abolished, this damn mess must stop. Your fiftieth birthday was to be in a few weeks, the opera village project in Africa needed ongoing work, and of course you had hoped to make a personal appearance in Venice next year, where you were to design the German biennial pavilion. It would have been an honor for you to represent the nation and to irritate it as well, to challenge and provoke.

Susanne Gaensheimer, curator of the German Pavilion, now probably has to ask herself whether Schlingensief without Schlingensief isn’t even worse and more impossible than Beuys without Beuys. Alas! Christoph, this damned lung cancer has torn you away from us much too early. That we will miss you is a lousy formula of mourning I can’t inflict on you even posthumously. But I need you to know up there on Cloud 24, or down there in the fires of Satan, that we already now suspect how great the loss is, how much the international culture scene will suffer because one of its leading initiators and contrarians has made his last exit.

Months ago, you wrote to me that “these fucking metastases were once again on the advance,” that “these little growth enthusiasts,” to whom you had already had to sacrifice your entire left lung, were up to mischief again, and that yet another chemo had failed to work. In an act of helplessness as much as piety, I took a printout of your e-mail, and unceremoniously pinned it to the wall next to my desk, directly beneath the framed photograph of the vigorously beating organ I had received at the last minute, shortly before your illness was diagnosed, thanks to a heart transplantation. Do you remember, Christoph, how, in 2008, during the first months after your surgery, we exchanged e-mails nonstop, hell-bent on sharing even the most intimate feelings, telling each other to have courage?

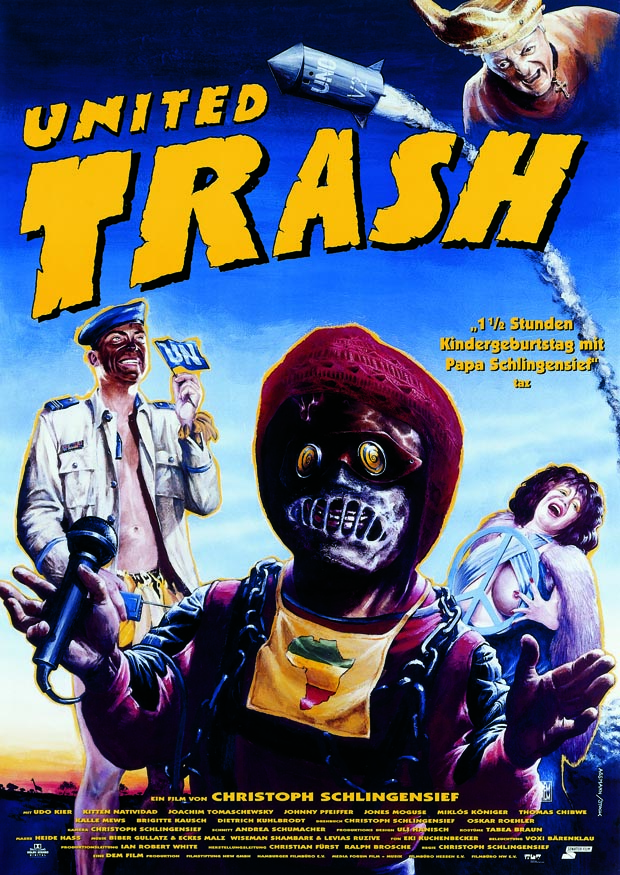

And so today I must write the last page of our correspondence, open a final chapter, by saying farewell. A chainsaw massacre, as it were. But how to pay tribute to you; how to encompass everything you have accomplished, how you stretched, and sometimes overstretched, the narrow idea of art? “Failure as Opportunity”—do you have any idea how much this slogan you propagated has ushered in a new way of thinking? What was weak, what met with little success or none at all—these marks of a loser, which society had once frowned upon, gradually really came to be understood, and not just by your fellow artists, as an opportunity to free life from the normative strictures of daily career rituals and transpose it into a different kind of value register. What was sensational, too, was how you—whose individual projects drew plenty of harsh criticism, including my own—straddled the disciplines and cast off the petit-bourgeois thinking in genres. Film, theater, opera, literature, the visual arts—hand in hand, arm in arm, head to head, or ass to ass. One gaffe after another.

And yet we’re both from most upstanding middle-class families, only children both of us, the sons of mothers named Anni who both gave birth to us, seven years apart, exactly on October 24, not knowing we would neither want to be pharmacists nor post office clerks. As narrow-gauge filmmakers, department of Super 8, or as altar boys, censers preferred, we went our separate as well as shared ways—you in Oberhausen, I, your senior, in Hanau in Hesse. Boy, the parallels we kept discovering by change. For a while I thought, pardon my English, that you were shitting me; it wasn’t possible, was it, that there would be someone out there whose biography, at least the milestones, was a virtual carbon copy of mine. These familiar paths running along similar lines no doubt proved a link between us, helping us get through even the rough patches when you would pull stunts from the cornucopia of perfidy, no holds barred, to the limits of what our relationship would bear.

I had to learn that you didn’t mean to hurt me and Gabriele personally—after we had helped you get a well-paid commission to direct a production—that your merciless, borderline, sometimes antisocial, even inhuman methods, not infrequently camouflaged as art, were directed against a system that struck you as questionable. But when you played the role of the smoothly polite son-in-law, be it at the Wagners’ in Bayreuth, be it on the (Berlinale’s) red carpet at home in Berlin, you often gave the impression that you didn’t in fact mind the pomp and circumstance at all. Yes, you were a player on the social stage, and you played people, too, dear Christoph, and before your illness led Gabriele to judge you with a certain leniency, she would often say that a player and cheat like you could not but burn in hell later on. That, she thought, would only be fair.

But today, one day after your unspeakable exodus from the world of culture, which is saddening to all of us, let us be hopeful and assume that you will end up above—for your recent good deeds, in Africa, if for nothing else. A Burkina Faso indulgence, that is to say. In your book entitled So schön wie hier kann’s im Himmel gar nicht sein! [It couldn’t possibly be as lovely in heaven as it is here!], you made the astonishing admission that there are various rules. “There’s a boundary one must not transgress,” you write on page 175, “lest one open the door to one’s own disintegration.” Little wonder, then, that you—whom many people would describe as an artist ruthlessly possessed by his ideas, including the controversial work with your disabled “freak stars”—were occasionally able to feel your secretly soft heart.

Of all days, on Christmas Eve of 2007—hardly an accident, I would think—you, the bastard, sent a sort of apology to Gabriele and me for an earlier collaboration at Berlin’s Volksbühne that had been most grueling, with a lot of backstabbing on your part. The project, your lines read, had “not exactly been the crowning achievement of my athletic endeavors.” That showed true greatness, quite in contrast with the cowardly retreat you beat in February 2005, something we will not soon forget. It was quite the lesson, and we were beside ourselves. My heart, already weak at the time, was twitching.

What remains, dear Christoph, are the profound memories of a man who—like few others—showed us time and again in his untiring creative work, whether it tended toward construction or destruction, what art can do, should be, could be. An existential balancing artist is what you were, a tightrope walker who feared no height—though you always knew that the danger of falling was dialectically tied in with any flight of creative euphoria. Intoxicated with the theatrical productions of life and death, you conducted your noisy acrobatic exercises on this earth or a few feet above, were able to conduct them longer than the severity of your illness had allowed us to expect. Now the time has come for eternal quiet. Away with the megaphone! Silence—silence, too, outside on this Sunday morning shortly after ten. I hope we will see each other one day on Cloud 24. Then, Scorpio brother, you can finally answer me these questions: Why was your poison stinger longer than mine? And looking back, were your claw attacks worth it, personally and socially? That’s a balance you still need to draw up. You’re getting detention, Christoph! Affectionately yours, Carlo

Karlheinz Schmid for Christoph Schlingensief. Obituary. KUNSTZEITUNG 169, September 2010

A preprint from the book accompanying the German Pavilion © German Pavilion, Sternberg Press