I first met Christoph Schlingensief in 1987, when he cast me for his film Schafe in Wales

[Sheep in Wales]. He was still fairly unknown at the time, and at first glance he struck me

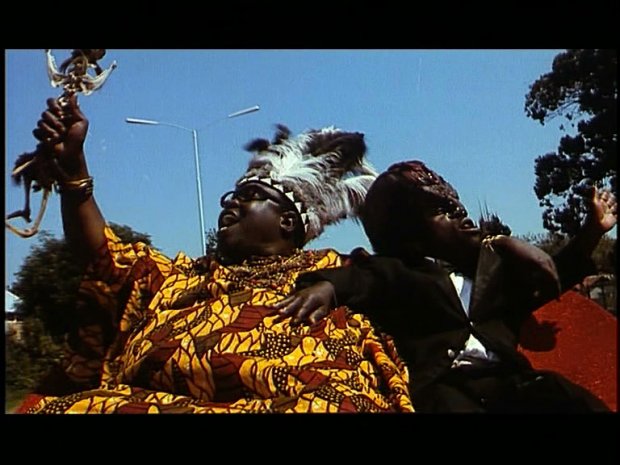

as a good-looking young middle-class man who had manners; every mother-in-law’s perfect dream. Yet behind the bourgeois façade lurked a great seducer, who would use his overwhelming charm to drive me into the craziest acts of self-abandonment, something I had not experienced since my time with Rainer Werner Fassbinder. After Fassbinder, with whom I spent a formative chapter of my life, from 1966 until his death in June 1981, and to whom I owe my very personal “Éducation sentimentale” in matters artistic as well as personal, working with Christoph now cast a similarly fascinating spell over me that mixed pleasure, fear, and curiosity. aking part in one of his projects—he always needed to exert all his charm to persuade me to do it—invariably meant embarking on a trip into the unknown, meant leaping into chaos and hoping that one would eventually emerge unscathed. There were no scripts but inspiring texts aplenty that were tried out and discarded, snippets of film and conversations that developed into scenes and video projections and gradually condensed into a multimedia collage.

Berliner Republik, at Berlin’s Volksbühne, was his first play in which I appeared. He always participated in the acting, was the motor and connector in a loose scenic aggregate. As long as he was the animator, this sort of evening could never really go awry. Repetition bored him, and so he came up with the idea of playing Berliner Republik backward. Five minutes before the curtain would rise he jumbled up the entire sequence of the scenes, and each actor had to see for himself how he would manage the transitions creatively. There were holes that were painfully embarrassing—the audience suffered with us—but also wonderful moments of realistic tension, something one cannot experience on any other stage. Working with him was always most challenging, and we never stood on the firm ground of a finished production. During the performances he would constantly come up with new things that demanded a response, and woe to him who laughed about that, something he did not like at all. He was a berserker and a magician at once. His surprise appearance in Atta Atta , for instance, was magnificent: I am soliloquizing with a flower in my hand, and suddenly he approaches me, covered in white powder and wearing a gigantic set of antlers on his head, moving spastically, throws me into a bathtub on the stage, and “rapes” me. When our mutual “feeling” on the stage was right, it was wonderful. Much of it, after all, played out on the level of the unconscious—it was inexpressible.

This mixture of the Catholic pharmacist’s son and the “abysses” inside him often shocked me. Sometimes I was afraid. When he worked with you, he would sense any weakness, any lack of conscious awareness in you, and use it. “Show your wound,” that was the credo he had adopted from Beuys, and after he was diagnosed with cancer, he worked maniacally, more alive than ever, calling himself into question as well and addressing his innermost feelings head-on in Church of Fear and Mea Culpa. During the long time that I worked with him, my view was often obscured by the hardships that being part of his productions entailed, and he did not seem all that great to me, but now that he is no longer I see the void he has left and realize that he was a giant. That is the one thing I would still like to tell him.

Irm Hermann for Christoph Schlingensief. From the book accompanying the German Pavilion 2011, Sternberg Press (ISBN 978-1-934105-42-9).