Jewish tombs in the twelfth century bear an emblem: a hare. In 1943, the symbol on the stones attracted the attention of Oberrottenführer Hartmut Mielke when his convoy was bulldozing Jewish cemeteries in central Germany so that the sites could be used for the construction of water tanks for fire trucks. The motif returns on tombstones from the seventeenth century: outstretched, prone hares “sleeping” or “slain.”

The Oberrottenführer, who was a dedicated local historian in his spare time, knew that this use contrasted with pagan depictions of hares in Celtic areas south of the Rhön Mountains, where hares are documented as appearing on sacrificial stone altars, but not on tombs.

In an article in the Zeitschrift für deutsche Vorzeitforschung [Journal of German Prehistoric Studies], vol. 14 (1809), 143ff., Alfred-Erwin Jahn, cousin of Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, the “father of gymnastics,” had already described the collision between the “hare” as a symbol of fertility (in a spring myth associated with the goddess Ostara) and the “theatricality of Golgotha”: the “somber departure of the son of God, who will not return for a long time.”

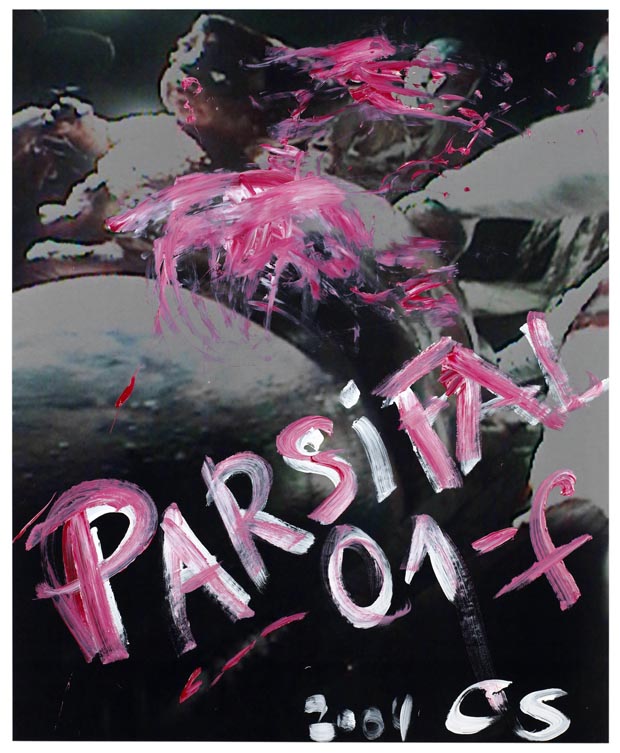

It was from this passage that Richard Wagner drew inspiration for the Good Friday spell he inserted into the third act of his Parsifal. The suffering of the cross and the mirth of “nature’s vernal laughter”: the contrast seemed to him an apposite expression of the “taxing burden of compassion.”Christoph Schlingensief now seized the scene Wagner had conceptualized through this perspective when he was working on his production of Parsifal in Bayreuth. He had long searched the score and the texts associated with the opera for something that would touch his heart.

A slain hare, bought from a business specializing in game meat, was taken to a basement at Berlin’s Humboldt University, where it was given over to the process of putrefaction for several weeks. At the behest of Kairos-Film, Walter Lenertz set up a 35mm Arriflex camera equipped with a time-lapse motor. The lighting was arranged. Care was taken that there would be flies in the chamber. The camera recorded the decomposition of the carcass at regular intervals for a number of weeks.

The experiment confirmed an insight from Walter Benjamin’s The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Benjamin discusses a metaphor that everyday consciousness finds hard to bear: the hairy animal body bursts open, broken apart by living and liquefied forces, so-called worms, at work on its inside. The skeleton comes to the surface. It was of such “necrotizing nature” in which “new life” is already “forming zealously” that the time-lapse camera gave account. It turned out that Benjamin was right when he called “the intensity of maggots of various sizes breaking out all over the ruined landscape of the former hare” a cause for consternation.

The sight of the decomposing hare, displayed in a large-format projection during the “Good Friday spell,” was profoundly discomforting to the festival audience in Bayreuth. After all, what they saw was not the “resurrection” of a hare but the “continuation of life in the forms of decay”: others live on what has died. In the end, the hare had undergone liquefaction; worms teemed in it, they, too, “doomed to die,” for after consuming the hare they were left without further sustenance in their basement compartment. That was HARD TO BEAR AS A MEANS OF EVENING ENTERTAINMENT, but quite apposite as a contribution to the establishment of the truth.

During the international press conference after the dress rehearsal, Schlingensief rejected the charge of “pessimism” leveled against his concept. He found himself incapable of seeing the greed with which the maggots captured by the camera clung to life as either pessimistic or optimistic. Rather, he said, it was positive that the camera could record such things, enabling the process to be repeated ad infinitum in the minds of future observers. If that wasn’t something like “rebirth”! “Conquering the conqueror.” The seriousness of the music, he said, proved it; there was no presenting it without giving offence. Wagner’s music, tamed by Pierre Boulez, proved incapable of mitigating the shock.

From the book accompanying the German Pavilion © German Pavilion / Sternberg Press 2011. A German version of this text was first published in:

Alexander Kluge, Das Bohren harter Bretter: 133 politische Geschichten (Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag, 2011)